November 19, 2021 — Abduljabbaar Hussein was a lawyer who devoted his life to fighting for the human rights of Ethiopian citizens, and was best known for his work defending high-profile political prisoners, including Oromo prisoners, who make up approximately 60% of Ethiopia’s population. When he was found in Adama City, Oromia, unconscious and in an area his wife claimed he never traveled to, she knew that he had not died of natural causes. This had happened too many times before. Although the news of his death spread quickly over social media, his family’s calls for justice have gone unheeded by the Ethiopian government and the Oromo community.

Abduljabbaar’s Legacy

Abduljabaar Hussein was born in 1980 in the Bale zone, Oromia. He received his LLB from Addis Ababa University in 2003. In addition to his work as a human rights defender, he also served as a judge in West Hararge zone and as a Judicial Trainer at the Oromia Justice Professionals’ Training and Legal Research Institute.

Throughout his career, Abduljabaar showed his devotion to human rights by taking on cases that other lawyers would not, even in the face of threats to his own life. For example, in 1998, he represented a group of 50 Oromo students who had been expelled from Addis Ababa University, despite the fact that it meant he had to go into hiding for six months. He is best known for his work defending high-profile political prisoners under multiple Ethiopian regimes. Notable clients included Lidetu Ayalew, an influential Amhara politician, and, most recently, the Oromo political prisoners Jawar Mohammed, Bekele Gerba, and Hamza Borena, who were arrested following the murder of the Oromo singer and activist, Hachalu Hundessa, in June 2020.

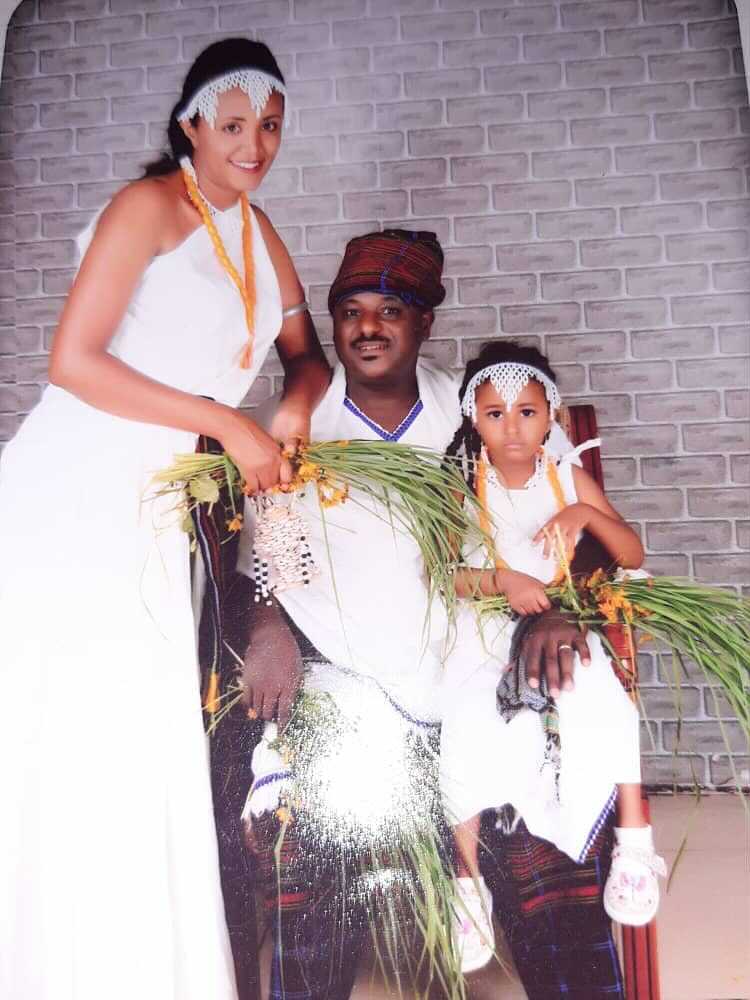

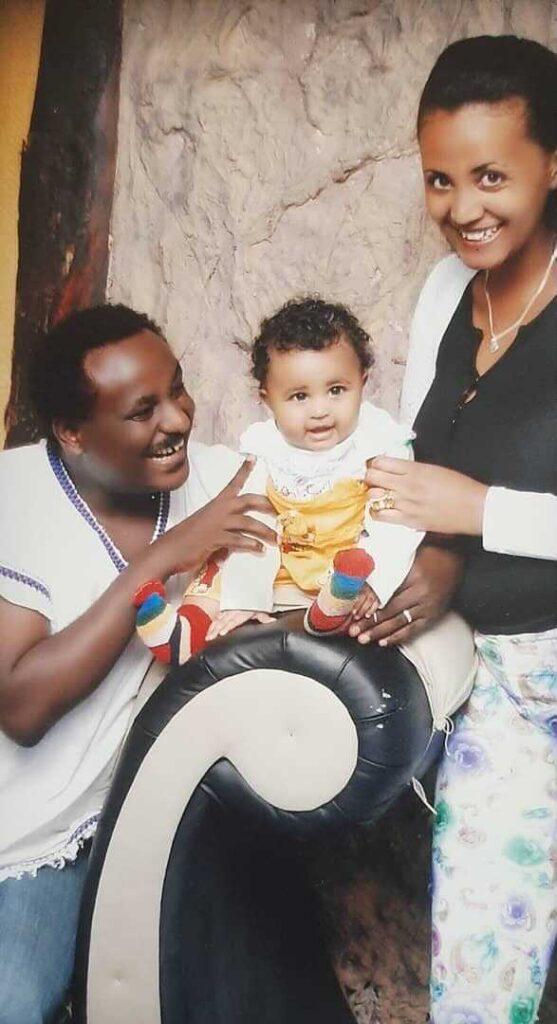

Abduljabbaar Hussein and his family

Abudljabaar’s Final Day

On the morning of August 11, 2021, Abduljabbaar ate breakfast with his wife, Soriya Kadir, and their 8-year-old daughter before heading to work. He was planning to meet with clients, who had been detained in police stations throughout Adama city. According to Soriya, he would call home around lunchtime every day, but that day he did not call. He did leave a comment on a picture she posted on Facebook around 4 pm, stating, “i love you my wife and daughter.”

Abduljabbaar usually returned home around 8 pm, but Soriya was surprised to receive a call from a stranger around 7:40, telling her they had found a man lying in the road, and asking if she knew him. Fearful that the stranger was talking about her husband, she told the stranger that he had blood sugar and asked them to give him sugar or a soda. Soriya then sent a taxi to pick Abduljabbaar up and take him to the hospital while she rushed to join them. Soriya arrived at the scene while her husband’s body was being loaded into the taxi. She could not see his upper body, but noted that his clothes were soaked and that his phone was missing. They quickly drove to a nearby hospital, where police were waiting for them. The police ordered Soriya and the taxi driver not to remove Abduljabbar from the car, checked his eyes with the flashlight on their mobile phones, and declared that he had died.

Soriya was devastated by this news, although she had long feared that this day would come, and had been operating in a state of panic and shock since the moment she had spoken to the stranger on the phone. She just remembers thinking to herself, “Where Jabbaar allegedly fell or was found is a dirty place full of drugs. Jabbaar does not pass through such an area.” She didn’t believe he had died of natural causes, and thought his body must have been dumped there by whoever attacked him.

Reporting Surrounding Abduljabbaar’s Death

Word of Abduljabbar’s passing began spreading through social media minutes after he was declared dead, and it came as a great shock to millions of Oromo. They all knew Abduljabbaar because of his work defending Oromo activists, and quickly began to question the cause of his death. OLLAA’s Executive Director, Seenaa Jimjimo, remembers wondering, “How could such a brave and brilliant lawyer, who defended Bekele Gerba and managed to survive the brutal TPLF regime of one of the worst African dictators have died so suddenly under a so-called Oromo government?” The diaspora Oromo community immediately suspected that he might have been murdered, just as Hachalu Hundessa had been a year earlier.

The next day, only one independent and credible print media source, the Addis Standard, published an article on Abduljabbaar’s death. In the article, they noted his wife’s request to the stranger who found Abduljabbaar to give him sugar, and quoted two individuals who claimed that he had no visible injuries, despite the fact that neither had seen his body. Some readers took this as a signal that Abduljabbaar had died of natural causes, and Soriya questioned why they would jump to such a conclusion prior to the conclusion of any official police investigation.

In contrast, Sheik Guutamaa Kaliil Boruu, a religious leader who washed Abduljabbaar’s body, told OLLAA that, when he first went to clean the body, it was covered in blood, and that, while Abduljabbaar had some cuts that were consistent with those performed during an autopsy, such as the opening in his chest, he also had multiple cuts to the back of his head. Sheik Guutamaa believes the wounds to the back of his head were consistent with stab wounds, and may have caused his death. He reports that the funeral services had to be delayed because they couldn’t get Abduljabbaar to stop bleeding, and that Ethiopian security agents monitored the entire washing process in order to ensure that they did not report what they had seen or take pictures.

Soriya followed Muslim tradition and did not attend her husband’s funeral. However, despite concerns for his safety, Sheik Guutamaa spoke publicly about what he had seen at Abduljabbaar’s burial. At the insistence of his community, he immediately went into hiding following his speech, and has since fled Ethiopia. OLLAA has received reports from a credible source that the Ethiopian government was searching for him following the funeral, as his speech prompted a public call for justice from the Oromo community.

A follow-up report by the Addis Standard noted “the controversy that erupted on social media after a religious leader’s comments on Abdul Jabir’s funeral”, and quoted Abduljabbaar’s brother, Sultan Hussein, as saying, “his wife told us that there were no injuries on his body”. When she was asked about Sultan’s statement by OLLAA staff, Soriya disputed his claims, stating that “his brother spoke without any authority and evidence,” and that he did not speak to her about her husband’s death and he had not seen Abduljabbaar’s body, either when he was brought to the hospital or while his body was being cleaned.

Soriya’s Call for Justice

According to Soriya, who recently spoke to OLLAA, Abduljabbaar had long faced death threats and intimidation because of his work. These had increased shortly before his death, when he had received numerous calls from unknown persons, warning him that he needed to withdraw from his representation of Jawar Mohammed and his colleagues, and telling him not to give the media updates on the case:

“Every time he was late, or he did not call, I suspected they got him. Even my family and our neighbor knew he would be murdered soon. They had tried to tell him. I told him my worries too. They told me many times why don’t you stop your husband? Why don’t you save your family and raise your only child? Government security forces called him all the time to intimidate him, to watch out that they are coming for him.” – Soriya Kadir

Soriya believes government security forces attacked her husband because of his work and left him for dead. She never received the results of the autopsy conducted at Milinik hospital, and has not contacted the police since his death, as she fears for her life as well. Ultimately, she wants the persons who killed her husband to be charged and brought to justice.

Today, Soriya has chosen to speak out about her husband’s death because of her hope that it will spur the Oromo to action. She believes that, not only was her husband murdered by the Ethiopian government, but that the people who he devoted his life to defending abandoned him by failing to call for justice following his death. Her plea today is not with the Ethiopian government, but rather to Oromo people who think her husband died from natural causes. She wants Oromos and the world to know he was murdered.

Conclusions

What is, perhaps, most striking about this case is that it is not unique. The Oromo have long complained of human rights abuses being committed against them with impunity, including extrajudicial executions. Similarly, prominent Oromo activists have also been killed under mysterious circumstances, including the singer, Hachalu Hundessa, in June 2020. However, where this case differs is in the level of attention given to his death by the Oromo and the international community. The news of Hachalu’s murder sent a massive shockwave throughout the world. Within 24 hours, hundreds of protesters were dead, while thousands were arrested, including Jawar Mohammed, one of Abduljabbaar’s clients. To this day, millions of Oromos and other Ethiopians have continued their calls for an independent investigation into the murder of Hachalu, while the Oromo have responded to the death of Abduljabbaar with silence, according to Soriya.

On the surface level, there may appear to be reasons to believe that Abduljabaar’s death was likely due to natural causes. While it may be unusual for a man in the prime of his life to drop dead in the street, it is not unheard of, and Abduljabbaar may have had diabetes, as initially suggested by his wife’s request that the stranger give him sugar. Likewise, multiple people were willing to give statements to media sources claiming that he had no visible injuries before he was taken to the hospital.

However, it also does Abduljabbaar, a man who stood as a symbol of courage and bravery for his work as a human rights defender, a disservice to overlook the factors that suggest a more nefarious end. We know that he had long faced threats and intimidation for his work, which had only increased since he started representing Jawar Mohammed, and that vocal Oromo activists had been murdered before. He had not called his wife during the day, as was his daily habit. What’s more, his body was found in a part of town that he reportedly never visited, he was soaked, and his phone was missing. The comments of Sheik Guutamaa regarding the condition of Abduljabaar’s body, coming from a man who had nothing to gain from spreading rumors about the cause of Abduljabaar’s death, and was forced to flee the country following his remarks, also cannot be ignored. At the very least, these factors make it clear that there should be an investigation into his death, and that his autopsy should be released to the public.

We must never forget Abduljabbaar, a brave, passionate human rights lawyer who fought for the rights of political prisoners for 25 years before his untimely demise. Despite his legacy, the Oromo has failed to give his passing the attention it deserves, and as such, the Ethiopian government has not felt pressured to launch an investigation into his death or release his autopsy report. The only hope Soriya has for justice is for the Oromo people to come together to demand an independent investigation. Unfortunately, given the lack of attention to his death thus far, it seems likely that her call for justice will remain unanswered.