This is the third installment in our series on Oromo migrants and refugees in Yemen. Here we delve into the dark history behind the route taken by these migrants – where not so long ago Oromo slaves were trafficked from Ethiopia and into the Gulf countries.

Worn-out flip-flops and calloused feet mark the young men and women making their way along the barren, dusty road from Obock to Aden. It is a trek that takes more than two days on foot, typically under a burning sun that pushes temperatures to 40℃ or more. There is little food or water to be found along the way. Instead, migrants rely on the kindness of locals or the black-and-white survival sacks handed out by the IOM at various checkpoints.

According to the IOM, at least 400,000 Ethiopians made this journey to the Arabian peninsula between 2017 and 2020. Since then, migration has slowed due to COVID-19 border restrictions. However, as these restrictions lift, the migratory flow is predicted to keep on growing. Key drivers such as low employment, ongoing conflicts and natural hazards remain unresolved.

A notorious route

This mass movement of people is no recent phenomenon. According to an interview with a people smuggler operating out of Yemen conducted by France 24 in February 2020, Oromos have been taking this road for hundreds of years:

“It’s basically the same road. Slaves were brought in from Ethiopia. The slave trade started in Ethiopia, went to Yemen, and mostly to Saudia Arabia.”

Today, there are two main versions of this journey; described in the documentary as the long route and the short route. The question of which to take comes down to necessity. On the longer route, migrants travel by car – these tend to be wealthier migrants, often coming from the more northern regions of Ethiopia.

“Then you have the short route, which is used by Oromos. And the Oromos don’t have a lot of money, they can’t afford to travel by car. So they walk. All of this, they do it on foot.”

It is a notoriously dangerous journey. Some do not make the trek – the heat, lack of water and exhaustion are already a death sentence. But even for those that make it to Aden or other towns, it is a bittersweet arrival. All too often what awaits them is abduction, torture and exploitation, or worse.

Today, we want to pay tribute to the young men, women and children who made the dangerous journey not in the desperate hope of a better life across the Gulf, but bound by the chains of a once highly active slave trade. Centered around the infamous slave markets in Aden, its a legacy can be seen in the rampant human-trafficking and exploitation that continues today.

Through doing so we hope to shed light on an uncomfortable past that is not so distant – nor so unfamiliar – as we would like to think.

Bound in chains: the East African slave trade

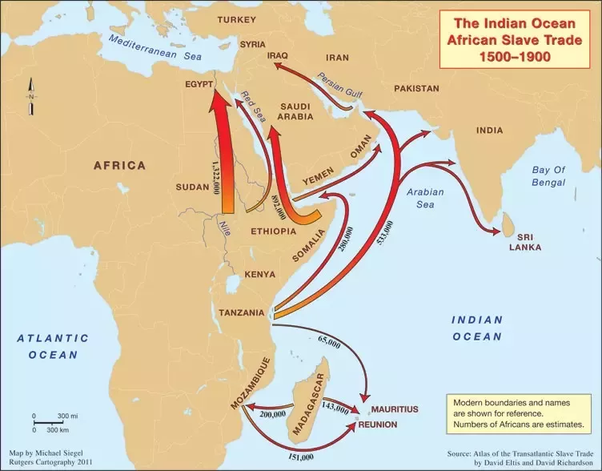

The East African slave trade, better known by the broader term Indian Ocean slave trade, is relatively unheard of amongst modern readers. And yet, it continued to operate until the beginning of the 20th Century – unlike the Atlantic slave trade which had already come to an end towards the middle of the 19th century.

Despite its relative anonymity, the Indian Ocean slave trade operated over a vast area, with three primary circuits. There was the African circuit, which covered East Africa, Madagascar and the Mascarene Islands; the South Asian circuit, which covered the Indian Subcontinent; and the Southeast Asian circuit of Malaysia, Indonesia, New Guinea, and the southern Philippines.

In part, this lack of notoriety is due to the much smaller quantity of available written material about the Indian Ocean slave trade. This lack of documentation also makes it difficult to be sure about exact figures, however most recents estimates suggest between 186,000 to 216,000 slaves were exported by Europeans from East Africa alone from 1670 to 1848.

A historical basis: the Ethiopian context

The Indian Ocean slave trade also has much deeper roots than its Atlantic counterpart.

Historical inscriptions suggest that the practise of slavery extends all the way back to 1495 B.C in the Ethiopia region – many centuries before the onset of the Atlantic slave trade. The Fetha Nagast (The Law of the Kings), a traditional law for Ethiopian Christians, is one of the first written laws regulating slavery. Translated from the 13th Century Arabic writings of a Coptic Egyptian writer, Abu-l Fada’il Ibn at- ‘Assal, it reads:

“[[t]he state of] Liberty is in accord with the law of reason, for all men share liberty on the basis of natural law. But war and the strength of horses bring some to the service of others, because the law of war and of victory makes the vanquished slaves of the victors.”

Despite already advancing (limited) notions of universal liberty, this law enabled the legal enslavement of certain categories of people, such as prisoners of war, non-believers and the children of slaves. It also included some relatively detailed regulations on the rights of these slaves.

Oromo attitudes to slavery

Yet, in contrast to this, some experts claim that the traditional Oromo religion and Gadaa system were strictly opposed to slavery. Professor of Philosophy at Addis Ababa University, Workineh Kelbessa, writes:

“The Oromo ethics opposes the unlimited exploitation of natural resources and inhuman treatment of fellow human beings. The Oromo religion and the Gadaa system are against all forms of slavery and slave trade. In the past, a person who committed the crime of selling a human being would not be allowed to participate in a ya’a—a pilgrimage to the seat of Oromo traditional religious leader, the Abbaa Muuda”

As slavery became a widespread practise in Ethiopia this would eventually change, but historian Mekuria Bulcha asserts that it wasn’t until the 19th century that Oromos owned slaves: “[a]lthough Abyssinians raided the Oromo for captives from the seventeenth century on, it seems that the Oromo did not own slaves until the nineteenth century”.

This shows that despite being a well-ingrained practice in the region, slavery was by no means universally accepted.

More recent accounts suggest that forms of non-free labor probably did exist in the southern regions of modern day Ethiopia. However, they affirm that it was with the southern conquests of Emperor Menelik II at the end of the 19th century with the imposition of the Gabbar system (which involved confiscating indigenous territories and enforcing a tribute system) that slavery became widespread in the Southern territories. It was this “unremmiting exploitation of the peasantry” that resulted in a growing human trade; as children were forced into slavery when the peasant population was unable to pay the heavy taxes demanded of them by the Emperor.

Those that came before: the fate of Oromo slaves

Sandra Rowoldt Shell’s 2018 book, Children of hope : the odyssey of the Oromo slaves from Ethiopia to South Africa, is a groundbreaking account of the lives of 204 Oromo children who were discovered by a Royal Navy fleet intercepting three dhows (traditional sailing boats) in an anti-slavery mission in 1888.

Despite being taken from the grips of slave traders, the story remains a tragic one for the vast majority of the young Oromos. Taken from their homes in the highlands in Oromia, these young boys and girls had already been forced to walk at least 700km to reach the coast before being placed into three crowded boats headed for the Arabian slave markets.

Once they were taken to Aden – in what is a cruel mimicry of today’s reality – many had already been greatly weakened by the arduous journey. After two years of being cared for by the Free Church of Scotland mission at Sheikh Othman, only 64 out of the original 204 survived. The survivors were then transferred to the Free Church of Scotland’s Lovedale Institution, in Alice, a town in South Africa’s Eastern Cape, where they proved to be good students and would go on to pursue a wide range of careers.

Conclusions

Remembering the many Oromo children and young people lost to the brutal industry of slavery not so long ago, brings into glaring light the uncomfortable realities of what is occurring today.

The thriving human trafficking trade along the Eastern Route – its harsh conditions of brutal exploitation, torture, sexual violence, or simply death from exhaustion, poor conditions and dangerous journeys – has clear parallels to the slave trade that predates it.

As our reports on survivors of the March Houthi bombing reveal – it is those who are most vulnerable that risk being lost to this abominable industry of human exploitation.

OLLAA continues to urge the international community, as well as the Yemeni and Ethiopian governments, to pay more attention to the plights of migrants and refugees and ensure they are treated humanely and with the dignity all human beings deserve.

Per survivors’ request for assistance with their medical expenses, we humbly ask you to support them directly HERE.