On October 2, 2016, millions of Oromos—an ethnic group descended from an ancient Cushitic-speaking people—gathered in Bishoftu, Ethiopia to celebrate the annual Irreecha thanksgiving festival. The day was supposed to be a joyous one, meant to observe the end of the rainy season and hail in the upcoming harvest through sacred rituals. Unfortunately, the festive atmosphere didn’t last long, and the events that followed have left behind a dark spot in the hearts and minds of millions of Oromos.

Irreecha is one of the most important holidays in Oromo culture, however the indigenous Oromo religion that it stems from – Waaqeffannaa – is little known outside of Ethiopia. In this exclusive, exactly six years on from the 2016 tragedy, we share the history of this ancient religion and its practitioners – a story of oppression and resistance that continues to this day.

We thank all those who gave their time to to share their knowledge with us, in particular Asnake T. Erko, Badri Adam and Muhammad Dekebo.

2016: A bomb ready to detonate

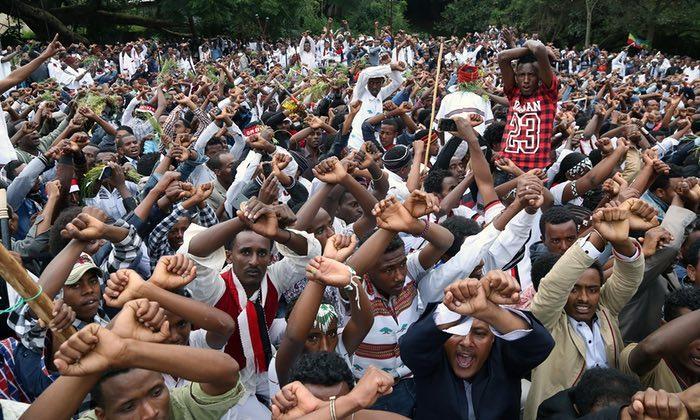

Tensions between the Ethiopian government and Oromo people had been gradually escalating over the previous four years. The government was concerned that Irreechaa – a holiday of such significance for the Oromo people – might undermine their authority. Armed government security forces were sent to keep watch over the event. In response to their presence, some attendants began to lead those gathered in anti-government chants.

The situation had become a bomb ready to detonate.

At first, the security forces used teargas, shooting indiscriminately into the crowds and watching as people ran in all directions, blinded by the gas and kicked-up-dust.. Screaming erupted as the teargas turned to bullets. There was a stampede as civilians desperately attempted to flee. Blockades had already been set up on exit roads, cutting off all main escapes.

“I was running with the crowd and was nearing the road and the person in front of me fell over,” one survivor recalled in chilling detail to the Human Rights Watch. “I tripped over him. I got up but he didn’t. I looked over and he had been shot and blood was pouring out of his neck. I was very scared.”

Some witnesses recounted people being trampled in the chaos. Others were forced to jump to their deaths from the edge of deep trenches or drowned as they attempted to swim to safety in a nearby lake. What should have been a jubilant occasion had turned into a bloodbath.

According to reports made by the Ethiopian government in the massacre’s aftermath, the total death toll was 55 people; opposition groups, however, placed it close to 700.

Defining Waaqeffannaa

The Waaqeffannaa religion is a foreign concept to the majority of westerners, but at over 6,000 years old and with millions of estimated modern-day practitioners, it is a fundamental part of Oromo culture and identity. A monotheistic religion, the term Waaqeffannaa derives from the name of the supreme being Waaqaa, who is known to be eternal, omniscient, and all-powerful. Per Waaqeffannaa teachings, Waaqaa’s creation of the universe began with water, which he further divided to create sky and earth. It’s believed that when one dies, they will go to be with him in ‘heaven,’ or waaqaa, lowercase.

Although Waaqeffattootaa (those who practice Waaqeffannaa) view Waaqaa as the only true God, it’s worth mentioning his comprehensive nature; Waaqaa is believed to be the same supreme being worshipped in other religions, even as he’s recognized by different names. This pluralistic understanding of Waaqaa is a driving force behind one of Waaqeffannaa’s key virtues: respect for all humans, regardless of cultural or ethnic background.

As Badri Adam, a Waaqeffannaa leader based in Toronto put it, “The idea of community is inclusive.” Humanity is viewed as one big family, every member of which is equally deserving of dignity and respect. “Human life has dignity,” Adam continued. “No matter what. It’s priceless. Being human is enough to make your life valuable.” As an offshoot of this, followers of Waaqeffannaa must strive to emulate the peace Waaqaa personifies. Peace for Waaqeffattootaa is not simply nonviolence, but actively caring for others.

It is worth noting that the respect and peace Waaqeffannaa teaches isn’t limited to humans alone. While humans are considered to be superior to other creatures, Waaqeffattootaa are also expected to respect Waaqaa’s other creations—animals, plants, and resources alike. Like social justice, environmental justice plays a major role in the religion; all living things are thought to be sacred, and humanity’s superiority comes with the responsibility to care for the earth and its non-human inhabitants. In the words of Adam, “Only use what you need, nothing more. Using more than is needed means you’re depleting the earth.”

Many aspects of Waaqeffannaa are echoed in the Abrahamic religions. There is one true being who created the world and all that exists within it. This being is the source of goodness and love, and humans should strive to follow these ideals. Man is considered superior to other creatures, and will go to be with Waaqaa or God in the afterlife.

Despite these similarities,Waaqeffannaa is distinct in many ways. Like many African traditional religions, it places emphasis on maintaining the balance of nature to a far greater degree than Abrahamic religions, and while the worship of physical objects is seen as sacrilegious, landscapes are valued for the symbolic role they play.

Importantly, Waaqeffannaa also has no text. Unlike the Christian Bible or Islamic Quran, Waaqeffattootaa rely on oral tradition to pass their beliefs to the next generations. This lack of written scripture has played a large role in fueling the misrepresentation of Waaqeffannaa by European scholars and others, who have for a long time been wont to label it as pagan, animistic, and Satanic. And these misunderstandings, as cultural misunderstandings tend to do, have played a large role in the historical suppression Waaqeffattootaa have experienced.

History

Abrahamic religions became widespread in Ethiopia in the 16th century, when invading Christian and Muslim powers fought for dominance ofthe region—a struggle that would continue for the next several centuries. During this time, Waaqeffattootaa found themselves pinned between these two opposing forces; some chose to convert to either Christianity or Islam, but the political and cultural upheaval allowed many to continue practicing Waaqeffannaa, even as the area’s religious landscape morphed.

It wasn’t until the 1870s that Waaqeffannaa was forbidden by the Ethiopian emperor, Menelik II, who was himself a member of the Christian Orthodox Church, and Christianity was promoted as the only legitimate religion. Traditional religions especially were considered to be heathen and uncivilized, and Oromo culture was suppressed as the imperial government pushed for a homogenization of newly Christian Ethiopia.

This, however, was just the beginning of state-sanctioned actions against Waaqeffannaa. Anti-Waaqeffannaa efforts escalated during the coming decades, hitting a peak during the 20th century. As human rights scholar Bedassa Gebissa Aga summarizes in his paper “Oromo Indigenous Religion,” during this period, “Oromo cultural and religious shrines and places of worship were condemned as pagan relics, deliberately destroyed and replaced by…Orthodox religious symbols, places of worship and cemeteries.”

Forced conversions were also widespread in the early 1900s, with the Ethiopian government mandating that millions of Oromos convert to Orthodox Christianity. “In resistance of foreceful conversion, some Oromors converted to Islam and others to Protestant Christianity,” Badri Adam explained. “Due to widespread discrimination and persecution,” prayer sites were also prohibited from being built, in addition to their active tearing down.

In 1974, Ethiopia again gained new leadership when the Derg regime seized power. Although the regime established an atheist government and formally banned all religions, Waaqeffannaa was still more harshly repressedthan Christianity or Islam. Waaqeffannaa prayer sites continued to be openly burnt, properties confiscated, and religious leaders and members killed or imprisoned.

While millions of Waaqeffattootaa were forced to convert throughout the 20th century, it’s worth noting that these conversions were frequently in name only. Many who publicly declared themselves to be Christian or Muslim converts continued to practice Waaqeffannaa in private. As such, Waaqeffannaa remained embedded into Oromo culture even as it was intensely suppressed, and organized revitalization efforts were able to develop in the 1990s. In 1998, the Macha Tulama Association founded “A Committee for Oromo History and Culture” (later renamed “Organization for the Followers of Waaqeffannaa”), which worked to revive Waaqeffannaa alongside other aspects of Oromo culture.

Present-day Persecution

The current legality of Waaqeffannaa is dubious. The 1995 Ethiopian Constitution Guarantees religious freedom, and Waaqeffannaa was legally recognized as an official religion in 2013. However, in practice, its religious status continues to be denied, with those who practice or are suspected of practicing routinely facing persecution.

Complicating the issue is the importance of Waaqeffannaa to the broader Oromo community, leading to the government conflating its practitioners with support for the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and Oromo nationalism. In recent years, part of the government’s efforts to crack down on the Oromo nationalism has been through the increased suppression of Waaqeffattootaa. As followers are often accused of being members of the OLF and similar opposition groups.

The Ethiopian government has also worked to dismantle the Gadaa system, a traditional Oromo form of democracy. The Gadaa system is embedded within Waaqeffannaa, and its presence has strengthened as the religion has become increasingly organized in recent years—in large part with the purpose of preserving Gadaa. Seeing the potential of localized democracy as a threat to authority, the Ethiopian government has attempted to quell it..

The ongoing suppression of Witaaqeffannaa has taken many forms. Waaqeffattootaa are denied burial rights, with land ownership of burial sites stripped away and requests for burial in public cemeteries or cemeteries affiliated with other religions often dismissed. Marriage rights are similarly denied, with traditional unions viewed as unofficial in the eyes of the law. Money and documents are frequently confiscated. Public perception, shaped by over a century of misinformation campaigns, propagates the unfounded stereotype that Waaqeffattootaa are devil worshippers and therefore should be condemned. Religious leaders are frequently arrested or murdered on the grounds of supposedly encouraging government opposition. To declare oneself a follower of Waaqeffannaa is to open oneself to potentially lethal reprisal.

Forced conversions also continue to this day. According to Adam, known Waaqeffattootaa are sometimes subjected to indoctrination and brainwashing techniques, the “success” of which is judged by their eventual condemnation of the Oromo religion. On top of indoctrination, children from families who practice Waaqeffannaa are denied access to education, and parents are penalized for failing to baptize them. “The family of my friend was forced to take all their children for baptism,” Adam recalled. “When the children are baptized, they are given Amharic names.”

Arguably most debilitating, Waaqeffattootaa are denied the right to practice their religion in public. Most of their places of worship that were destroyed in the 19th and 20th centuries were never rebuilt, and while the government is known to give land to organized religion for the purpose of worship and burial, Waaqeffannaa applications are almost always ignored. Although the past decade has seen some rise in public gathering spaces, few are willing to risk the ramifications that come with being identified as a follower of Waaqeffannaa, including harassment by local governments and security forces. Instead, people are forced to pray, teach, make religious observances, and execute traditional rituals in the secrecy of their own homes.

Holy days also go unobserved in public. “Within the last two years, we have not been able to perform our holidays,” Adam said. “Especially the biggest one, Ayyaanaa Worra Abba Oromo,” or the Oromo Ancestry Celebration Holiday, in which Oromo ancestors are honored and their continuing cultural presence remembered. Those who have gathered to celebrate this holiday have been broken up by security forces, and prohibited from meeting with other followers. Traditionally, this holiday is accompanied by a pilgrimage which serves as an opportunity for spiritual revival and cultural reconnection. For the past two years though, followers from across Oromia traveled hundreds of kilometers to the Daro Labu meeting point only to be turned away. This past year, the planning committee and other leaders were also jailed.

Irreecha is the only Waaqeffannaa holy day recognized by the government, but even that has been cut off from its religious roots – recognized as a strictly cultural holiday.

Most concerning are the killings of Waaqeffattootaa that the government continues to both condone and perpetrate. The world watched in horror when, in October of 2016, news of the violence against Irreecha festival attendees in Bishoftu spread. Accounts began to circulate online, including pictures and videos taken by survivors. Images show the panic on people’s faces as they fled from soldiers. People with their hands thrown in desperate surrender into the air. Bloodied bodies lying in the dirt. In videos, screams and rapid gunfire can be heard.

Once the killing spree had ended, witnesses reported military vehicles swooping in to collect the bodies, alongside some of the more severely wounded, before evidence could be gathered. Several of the festival’s attendees were arrested in the weeks that followed under suspicion of inciting anti-government chants; those interviewed by the Human Rights Watch reported being beaten by security forces during their detention, and were also denied any trial. More arrests occurred as protests swept through the country, and the government was forced to declare a state of emergency on October 9. Another state of emergency was put into place from April to August, 2017.

The latest dark day for Oromo and Waaqeffattootaa took place in Oromia’s Fantaalee District late last year. On December 1, 2021, hundreds in the Karayu Oromo community gathered for a Gadaa assembly. Like Irreecha, this assembly came to an abrupt end when Ethiopian security forces descended. 39 attendants were abducted and taken away, including the Abba Gadaa and Abba Boku—two religious leaders of huge importance to the Karayu community. Both these leaders, along with 12 other people, were executed later that afternoon. Aside from two people who were able to escape, the remaining abductees spent the next month in prison without trial, where yet another person died.

In the initial aftermath, the government denied responsibility, blaming the attack on the Oromo Liberation Army—an offshoot of the OLF. This declaration received public backlash, however, and two Ethiopian politicians argued against the claim. Angaasaa Ibraahim, a Member of Parliament for the Oromia Region, blamed the Oromia Police Commissioner, saying he had ordered the Oromia special police to carry out the arrests and killings. Taye Dendea Aredo, Ethiopia’s State Minister for Peace, also placed responsibility for the attack on the government

The Karayu massacre wasn’t the first time people were arrested for participating in the Gadaa ceremony. On August 23, 2011, over 150 were detained after gathering for the ceremonial transfer of Gadaa leadership from one generation to the next. One of those detained was a student at Adama University; as he reported to Amnesty International, “he had been [traveling] around the region to document the ceremony but was arrested on the accusation [of] trying to incite people to rebel against the government.”

In addition to these massacres and mass arrests, individuals are frequently extrajudicially executed, detained, or disappeared, though underreporting makes the prevalence of such instances difficult to determine.

Raising Awareness

Clearly, the persecution of Oromos and Waaqeffattootaa is an issue that must be addressed, but little has been done by the Ethiopian government to investigate or hold the perpetrators of such attacks accountable. This begs the question: Where do we go from here?

One of the biggest hurdles the Oromo community faces is the lack of local and foreign media coverage for the abuses they have experienced. While other Ethiopian issues—most notably the ongoing war in Tigray—have made headlines around the world, there has been overwhelming silence when it comes to human rights violations against Waaqeffattootaa and Oromos. Even the 2016 Irreecha massacre, despite such a high death toll and readily available footage, received minimal global coverage.

In part due to this lack of public awareness, international powers, including the US and the UN, have failed rto put pressure on the Ethiopian government regarding issues of Oromo rights. For example, following the Karayu massacre,the Oromo Legacy Leadership & Advocacy Association met with US government officials and asked them to condemn the atrocities being carried out against Waaqeffattootaa. Unfortunately, the State Department’s annual report on International Religious Freedom remade no mention of the attack against the Karayu.

A Story of Resistance

Despite the challenges the Waaqeffannaa community continues to face, the revitalization efforts that began in the late ’90s have continued. Following the government’s 2013 decision to recognize it as an official religion, Waaqeffannaa saw a mini revival. Between 2013 and 2015, religious leaders and followers pushed for Waaqeffannaa’s rekindling in the public sphere, an effort which included the opening of over a hundred galmoota ( places of worship). While public worship was and is a dangerous affair, these openings were a bold act of reclamation that physically marked the potential new era on the horizon. These years further ushered in a wave of public assemblies, including five national conferences alongside numerous local and regional gatherings.

In 2015, crackdowns on Waaqeffattootaa escalated once more as the government began to revert to its old ways. It was, in many senses, one step forward two steps back, culminating in the Irreecha massacre in 2016.

Even in the midst of these setbacks, it’s important to recognize that the Waaqeffannaa and Oromo communities have not passively accepted injustice. In the wake of the 2016 Irreecha killings, protests broke out across the country. Nonviolent acts of protest, including chants, marches, blockades, and boycotts remain popular among Oromos hoping to raise awareness and push back against human rights violations. Raising one’s arms above their heads and crossing them to form an X has become a symbol of Oromo resistance.

As the six-year anniversary of Irreecha arrives, it’s vital to recognize that the history of Waaqeffannaa is a dual one. Waaqeffattootaa have suffered oppression and marginalization. Persecution and slaughter. They’ve been made outcasts throughout the country. However, the decision to paint Waaqeffattootaa solely as victims would do them a great disservice.

Today, as we remember those who were killed in Bishoftu,those killed in Fantaalee, and the countless others lost in unreported but equally important instances, let us also remember the legacy they leave behind of strength in the face of great adversity.