As the conflict in Ethiopia engulfs the entire country, those forced to flee and seek asylum in neighboring countries face ever-greater barriers. For Oromo refugees and asylum seekers in Kenya, the quick footwork of the Refugee Affairs Secretariat (RAS) – which has changed location by hundreds of miles multiple times over the past year and a half – has become more than a source of fear and frustration; it is an almost impossible journey. Unfortunately, this is only the latest chapter in the longstanding challenges facing Ethiopian refugees in Kenya. As explored in this exclusive report, the long arm of the Ethiopian government has been making its way across the Kenyan border for many years. For those fleeing persecution back home, hopes for a safe haven can be quickly dashed.

OLLAA stands in solidarity with the Oromos refugees seeking asylum in Kenya, and calls on the Kenyan government to uphold its duties under international law and for international organizations to assist those in need. We also call for an independent investigation of human rights violations by the Ethiopian government both within and across its borders.

Background:

Kenya is home to a significant number of Oromo-Kenyans, as well as Ethiopian refugees predominantly originating from the Oromia and Ogaden regions of Ethiopia. According to the Danish Refugee Council (DFC), these refugees are typically fleeing political persecution and “escaping harsh, oppressive and undesirable conditions.” As the conflict in Ethiopia escalates, and as OLLAA has been documenting, thousands of Oromo civilians and political opponents face violent government targeting and arrest. With so many fleeing their homes in fear of their lives, OLLAA is deeply concerned by reports of the unwelcoming and obstructive practices currently in place.

Since 2014, Human Rights Watch (HRW) has been conducting research into the treatment of Ethiopian refugees and asylum seekers in Kenya. Their reports identify “a clear pattern of harassment”, abduction, and torture of refugees and asylum seekers by persons purporting to be Kenyan police officers or working for the Ethiopian government. This “long arm” of the Ethiopian government is deeply rooted in Kenya, with documented allegations of collaboration between Kenyan police and Ethiopian intelligence officers reaching back almost a decade. HRW has documented testimonies from several Kenyan police officers who received money from the Ethiopian embassy in Nairobi in exchange for locating Ethiopians. One source even stated to HRW in April 2016 that “we welcome them [refugees] here, because we know they are wanted by [the government of] Ethiopia, and the more there are, the more [money] we can make.” HRW’s former senior researcher on Ethiopia, Felix Horne, wrote that:

“Ethiopia’s intolerance of dissent has also been exported across the border in the past. For years, Ethiopian intelligence officials, sometimes in cooperation with Kenyan police, have harassed, threatened, and on occasion kidnapped Ethiopian asylum seekers in Nairobi and elsewhere in Kenya.”

According to HRW, and OLLAA’s own sources, it is the Oromo that have typically been at the receiving end of this treatment. Reports indicate that countless Oromos have been forcibly transferred from Kenya to Ethiopia, including refugees registered with the UNHCR, or even those holding foreign citizenships. Once in Ethiopia most face torture and detention.

Some of those abducted, like Mr. Dabasso Guyo, are never heard from again. Mr. Guyo, who was in his late seventies, was a prominent Oromo wisdom keeper, oral historian and spiritual leader who spent 30 years teaching Oromo culture and spirituality in Nairobi. He was abducted after giving a speech at the Irreecha festival in Nairobi in 2015. The targeting of civilians who have no known links to rebel militias, but simply seek to celebrate and share the Oromo culture with those around them, reveals the extent of the Ethiopian government’s hostility towards the Oromo people.

Unfortunately, the practice of targeting Ethiopian refugees in neighboring countries such as Kenya, Sudan, Somalia and Djibouti has continued under the leadership of current Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, particularly as the conflict within Ethiopia continues to spiral out of control. Since the outbreak of war in Tigray last year, it has been reported that Tigrayans have also been targeted by Ethiopian security forces in Nairobi.

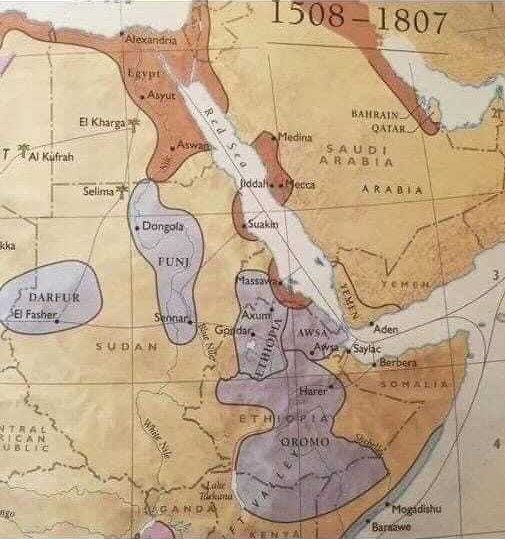

The Oromo in Kenya: Vestiges of a lost empire

Kenya is home to significant Oromo communities such as the Borana, Garba, Waata and Orma; Oromo tribes indiginous to Kenya. The border area between Ethiopia and Kenya is occupied by the Borana Oromos, who share the same language, religion, and cultural heritage. The only difference between these groups is the international demarcation that had placed them into different countries. However, it has been reported Boranas based in Kenya are often attacked by Ethiopian security forces, and that these attacks are ignored by Kenyan security forces. Furthermore, the areas in Borana are among the least developed communities in Kenya. According to OLLAA’s Executive Director, “It seems like Kenya has left that part of the country for the Ethiopian government to patrol as they wish – even if it means gross human rights violation against Kenyan citizens.”

Borana Oromos coming to Kenya from Ethiopia have heard reports of the Kenyan government collaborating with the Ethiopian government, and fear that they will be unsafe even though they speak the same language and share the same cultural heritage as the Kenyan Borana. For their part, Kenyan Oromos (Boranas) despair that they have no power to assist their brothers and sisters from the other side as they may be suspected of supporting the Oromo militia groups.

The Kenyan Government Plays Hide and Seek with Oromos Fleeing Conflict:

Despite the difficulties that Ethiopian refugees face in Kenya, the relative stability of the country, as well as kinship connections and established trafficking routes continue to make it an attractive option for migrants. However, strategic moves by the government body tasked with assessing refugees, the Refugee Affairs Secretariat (RAS), in what appears to OLLAA as a side-stepping of its international responsibilities, casts doubt on the prospects of those seeking asylum in Kenya during this current crisis.

The Refugee Affairs Secretariat in Kenya is the office tasked with assessing refugee claims. This means those wishing to be registered as refugees must call their office to arrange an in-person appointment to submit their asylum application, along with all necessary documentation, within 30 days of entry into Kenya. If their registration is successful, the RAS will then issue an asylum seeker pass and movement passes; allowing them to access services provided by the Kenyan government and UNHCR. Registered asylum seekers then must wait to complete a Refugee Status Determination interview, and if refugee status is granted, they can then partake of their rights under international law. Undocumented refugees and asylum seekers, on the hand, have no access to food, shelter or services, putting them at extremely high risk of harassment, exploitation and abuse.

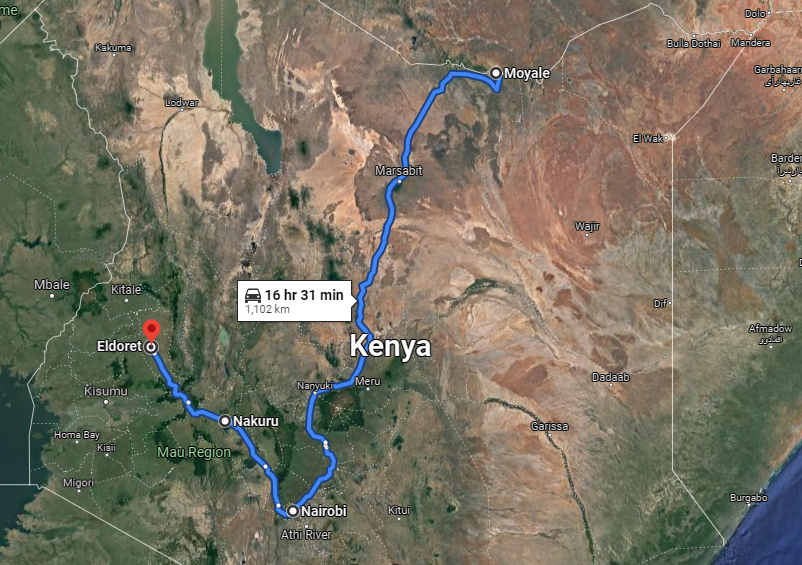

Citing concerns over the COVID-19 pandemic, the offices of the RAS and UNHCR Kenya closed to the public on 16 March 2020. This meant that the Kenyan government stopped registering asylum applications in Nairobi. Although asylum seekers were officially reallowed to register their applications for asylum in Nairobi again in October 2021, our sources state that prior to this the office mandated with registering new arrivals shifted from Nairobi to Nakuru, located some 170 km from the northwest capital, before moving it once again in 2021, to Eldoret town, 156km west of Nakuru.

This has meant that Ethiopian asylum seekers, mostly Oromos, entering from the Moyale border, are forced to travel hundreds of miles to register their applications, all while much more vulnerable due to their undocumented nature. As we can see in the map provided, those seeking refuge must traverse much of the country in order to be registered. Many fear being caught by police, and, as most have fled their homes in fear of their lives, are carrying very little with them. With the closure of offices, and the transferral of processing facilities across the county, OLLAA has received testimonies from Oromos who have made multiple attempts at being registered as refugees without success. One witness recounted to OLLAA that she has been waiting for an appointment with the RAS since July 2020, despite having her details taken down numerous times.

With a history of obstructing Ethiopian refugees, or, as hinted at above, of milking them for financial gain, it is perhaps no surprise to hear of the ubiquity of bribes in this process. OLLAA has received numerous allegations of asylum seekers being forced to pay bribes in order to have their applications registered, reportedly up to 30,000ksh (roughly US$265) in Nakuru and 10,000ksh in Eldoret town. In cases where asylum seekers cannot afford the bribes, asylum seekers are reportedly denied the opportunity to file their claims at all.

Legal Standards

It is a generally accepted international norm that asylum procedures must be fair and efficient and non-discriminatory in order to ensure a full and inclusive application of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refuges and the 1967 Protocol. OLLAA is concerned that several of the policies and practices adopted by the Kenyan government in the past few years have clearly not met those standards, and have effectively led to the denial of access to asylum procedures for Oromo asylum seekers. The practice of frequently moving RAS services to cities that are a great distance from asylum seekers both serves to confuse would-be asylum seekers about the appropriate procedure to follow in order to register their asylum application, and make it nearly impossible for them to reach these locales, especially when they do have not have access to travel documents.

The allegations that RAS employees have made asylum seekers pay bribes in order to have their applications entered into the system is also objectively unfair and likely a form of discrimiantion based on their ethnicity. Finally, the most recent reports that RAS employees are refusing to enter Oromos’ asylum applications into the system is also a form of discrimination and means that the Kenyan government has effectively denied these asylum seekers access to asylum procedures, leaving them in limbo.

The longstanding reports that Oromo refugees have been forcibly transferred from Kenya to Ethiopia, where they face torture and detention, may also violate the prohibition of refoulement. Under the 1951 Convention, States have a duty not to “expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” Similarly, the Convention Against Torture, which Ethiopia has ratified, also provides that a government may not “expel, return (‘refouler’) or extradite a person to another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture.”

Conclusions:

OLLAA is deeply concerned by these reports of discriminatory practices towards refugees and asylum seekers in Kenya. As the situation rapidly deteriorates across Ethiopia it is critical that space is made to welcome those fleeing conflict and persecution. Moreover, the longstanding issues facing Ethiopian refugees in Kenya; of harassment, abduction, torture and bribes, offers little chance for these refugees and asylum seekers to build new lives free from persecution.

OLLAA urgently encourages the UNHCR to fully investigate these allegations and all similar cases across Kenya. With plans for one of Kenya’s largest refugee centres, Kakuma, set to close within the next 6 months, we also urgently encourage the Kenyan government to open a refugee center near the Ethiopian-Kenyan border. This would go a long way towards protecting Ethiopian refugees from the risks associated with undocumented travel, and lessen the opportunities for exploitation by those seeking to profiteer from these vulnerable individuals.